ISSUE1732

- Mark Abramowicz, M.D., President has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

- Jean-Marie Pflomm, Pharm.D., Editor in Chief has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

- Amy Faucard, MLS, Associate Editor has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

- Review the available options for prevention of mosquito and tick bites in adults, children, and pregnant women.

- DEET is highly effective against mosquitoes and ticks and is generally safe.

- PPicaridin appears to be as effective against mosquitoes as similar concentrations of DEET and may be better tolerated on the skin. It also repels ticks.

- IR3535 at concentrations ≥10% can be effective in repelling mosquitoes and ticks.

- PMD (para-menthane-3,8-diol), the active ingredient in oil of lemon eucalyptus (OLE), has been as effective as DEET against mosquitoes in some studies. It is generally not recommended for use on children <3 years old.

- Citronella oil-based insect repellents provide short-term protection against mosquitoes, but not ticks. Other essential oils also provide limited protection against mosquitoes

- Wearing clothing treated with the insecticide permethrin in addition to using DEET or picaridin on exposed skin provides the most complete protection against mosquitoes and ticks.

- Wearable devices such as wristbands and patches are not effective.

Table

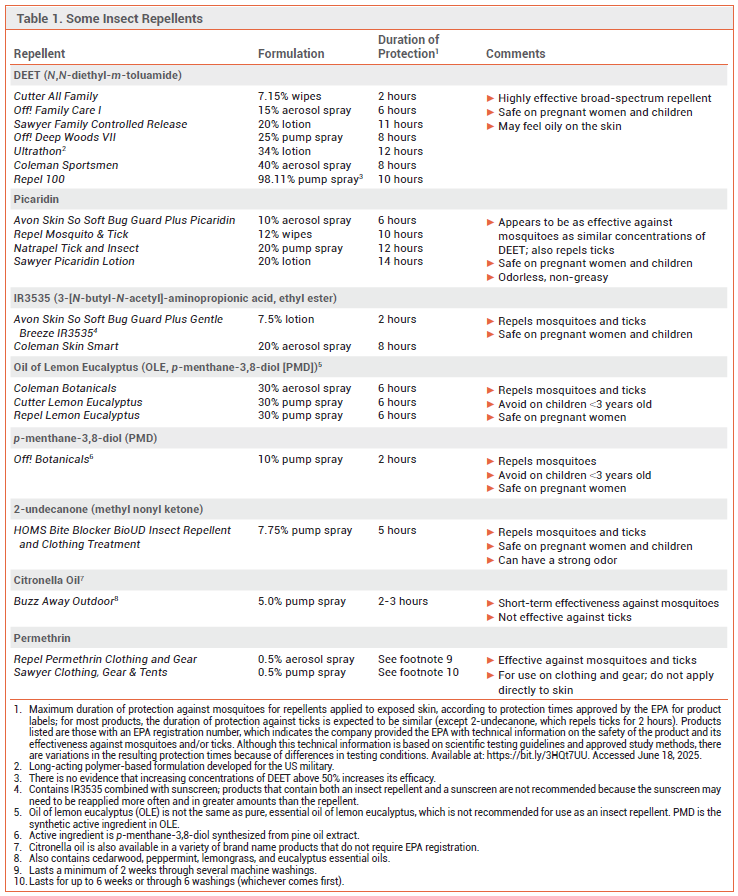

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recommend using insect repellents to avoid being bitten by mosquitoes, ticks, and other arthropods that transmit disease-causing pathogens. Repellents applied to exposed skin should be used in conjunction with other preventive measures such as wearing long-sleeved shirts, pants, and socks and avoiding outdoor activities during peak mosquito-biting times.1 Some insect repellents are listed in Table 1.

Mosquitoes can transmit pathogens such as Zika, chikungunya, dengue, West Nile, eastern equine encephalitis, and yellow fever viruses, and the malaria parasite. Biting midges (no-see-ums) and some mosquitoes can transmit Oropouche virus. Ticks can transmit the bacteria that cause Lyme disease and Rocky Mountain spotted fever, the parasite that causes babesiosis, and viruses such as Powassan virus.

DEET — The insect repellent N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide (DEET) is highly effective against mosquitoes and ticks.2 It also repels chiggers, fleas, and some flies, including biting midges and gnats, but not tsetse flies, which transmit the parasite that causes African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness). DEET is available in concentrations of 5-100%; higher concentrations typically provide longer-lasting protection, but increasing the concentration above 50% has not been shown to improve efficacy. Products containing ≤20% DEET provide 1-6 hours of protection. A long-acting polymer-based formulation containing 34% DEET has been shown to repel mosquitoes for up to 12 hours.

Topically applied DEET is generally safe.2 Toxic and allergic reactions have been uncommon, and serious adverse effects are rare.3 Rashes ranging from mild irritation to urticaria and bullous eruptions have been reported. A cohort study in US adults found no significant correlation between urinary levels of a DEET metabolite and biomarkers of systemic inflammation or immune, liver, or kidney function.4

Some DEET formulations feel uncomfortably oily or sticky on the skin. DEET can damage clothing made from synthetic fibers and plastics on eyeglass frames and watches.

Children – According to the CDC, DEET can be used on children without age restriction. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends using DEET sparingly on children ≤2 years old. Neurologic adverse events have occurred rarely in infants and children, usually with prolonged or excessive use that sometimes included ingestion of the product. Contact urticaria has been reported.5

PICARIDIN — Picaridin provides protection against mosquitoes, ticks, flies (including biting midges, but not tsetse flies), fleas, and chiggers. It is available in concentrations of 5-20%; higher concentrations typically provide longer-lasting protection. Picaridin appears to be at least as effective against mosquitoes as similar concentrations of DEET.6,7

Picaridin can cause skin and eye irritation, but it appears to be better tolerated on the skin than DEET. Picaridin is odorless and non-greasy; it does not damage fabric or plastic, but it can discolor leather and vinyl. In a review of data from US poison control centers, ingestion of picaridin-based insect repellents resulted in only minor toxicity (mainly ocular or oral irritation and vomiting) that did not require referral to a healthcare facility.8

Children – According to the CDC, picaridin can be used on children without age restriction.

IR3535 — IR3535 (3-[N-butyl-N-acetyl]-amino-propionic acid, ethyl ester), a synthetic version of beta-alanine, is available in the US in concentrations of 7.5% and 20%. It repels ticks, chiggers, and a variety of insects, including mosquitoes, sand flies, and biting midges. The 7.5% concentration provides limited protection (≤2 hours).9 The duration of protection is longer with higher concentrations (≥10%); products containing 20% concentrations have been shown to be effective for up to 8 hours. IR3535 can cause eye irritation, and it can damage some clothing and plastics.

Children – According to the CDC, IR3535 can be used on children without age restriction.

OIL OF LEMON EUCALYPTUS/PMD — Oil of lemon eucalyptus (OLE), which repels mosquitoes, ticks, flies, gnats, and biting midges, occurs naturally in the lemon eucalyptus tree. Extracted OLE is refined to increase the concentration of PMD (para-menthane-3,8-diol), its active ingredient. OLE is available in concentrations of 10-40%. It provides up to 6 hours of protection against mosquitoes.2 Synthetic PMD is also the active ingredient in some commercially available insect repellent products. Some PMD formulations have been as effective as DEET against mosquitoes in laboratory and field studies.10,11 OLE and PMD can cause eye and skin irritation, including allergic skin reactions. Oil of lemon eucalyptus essential oil is not recommended for use as an insect repellent.

Children – OLE and PMD insect repellent products are generally not recommended for use on children <3 years old because allergic skin reactions could occur, but according to the CDC, some products containing OLE as the only active ingredient can be used at concentrations up to 30%.12

2-UNDECANONE — 2-undecanone (methyl nonyl ketone) was originally derived from wild tomato plants. Data on its efficacy are limited. A 7.75% spray formulation that can be applied to skin, clothing, and outdoor gear (BioUD) repels mosquitoes for up to 5 hours and ticks for up to 2 hours according to its label. In field trials, BioUD has been comparable in efficacy to 25-30% concentrations of DEET and more effective than 0.5% permethrin.13,14 It can have a strong odor.

NOOTKATONE — A new active ingredient called nootkatone (NootkaShield) has been developed by the CDC in partnership with a private company.15 It repels and kills ticks and mosquitoes,16,17 and is registered as a biopesticide by the EPA for use in insecticides and insect repellents. Nootkatone is a natural compound found in grapefruit and Alaska yellow cedar trees that has been used for many years to make perfumes and colognes and as a flavoring in foods. In one laboratory study, 20% nootkatone was as effective at repelling mosquitoes as 7% DEET and 5% picaridin.18 Nootkatone-based repellent products are not currently available in the US.

CITRONELLA OIL — Citronella oil-based insect repellents, which are available for topical use in concentrations of 5-10%, provide short-term protection against mosquitoes, but they are not effective against ticks. The duration of protection with most citronella oil products is ≤2 hours; combining citronella oil with vanillin prolongs its protection time. In laboratory studies, mean protection time against mosquito bites was much shorter with citronella oil than with DEET. Eye and skin irritation can occur.5,19

OTHER ESSENTIAL OILS — Essential oils obtained from raw botanical material, including clove, geraniol, rosemary, and peppermint, provide limited and variable protection against mosquitoes. Five commercially available repellent sprays containing combinations of essential oils were tested in a controlled laboratory environment; mosquito attraction to humans was reduced for 30 minutes with four products and for 60 minutes with one.20 Another laboratory study evaluated the repellent efficacy of 20 essential oils against mosquitoes and ticks; 10% formulations of cinnamon oil and clove oil had the longest protection times (~120 minutes).19 High concentrations of essential oils can cause allergic contact dermatitis.21

FACTORS AFFECTING PROTECTION TIME — The actual duration of protection provided by a repellent depends on multiple factors, including the concentrations of active ingredients in the formulation, the amount of repellent applied, the activity level of the user, and environmental conditions. Studies have shown that consumers generally apply doses of insect repellent that are much lower than those applied in laboratory tests of the duration of repellent efficacy.10 A product's effectiveness may also be reduced by evaporation from the skin surface and wash-off by sweat.6

USE WITH SUNSCREENS — Topical insect repellents can be used with sunscreens; the repellent should be applied after the sunscreen. Applying DEET after sunscreen can reduce the sun protection factor (SPF) of the sunscreen, but applying sunscreen after DEET may increase absorption of DEET.22 Use of products that contain both a sunscreen and an insect repellent should be avoided because the sunscreen may need to be reapplied more often and in greater amounts than the repellent.

PERMETHRIN — A 0.5% formulation of the synthetic pyrethroid contact insecticide permethrin can be sprayed on clothing and gear (e.g., mosquito nets, tents, and sleeping bags) to repel and kill mosquitoes and ticks. It should not be applied directly to skin. Permethrin-impregnated clothing that remains active through multiple launderings is commercially available. Studies in outdoor workers wearing factory-treated, long-lasting permethrin-impregnated clothing have found that the clothing protected against mosquito and tick bites for at least 1 year.23,24 Wearing permethrin-treated clothing and using DEET or picaridin on exposed skin provides the most complete protection.25

Wearing permethrin-treated clothing results in dermal absorption, but the amount absorbed remains below EPA-recommended levels with up to 3 months of use26; no significant adverse effects have been reported.24 An analysis of urine samples from a cohort of US adults found that persons with higher urinary levels of a pyrethroid metabolite (due to environmental exposure from ingestion, inhalation, and/or dermal absorption) had an increased risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality compared to those with lower urinary levels of the metabolite (HR 1.56 and 3.00, respectively).27

WEARABLE DEVICES — Several insect repellents, including DEET, OLE, and citronella, are commercially available in wearable devices such as wristbands and patches. These devices have been shown to provide little or no protection against mosquito bites.25,28

PREGNANCY — The CDC considers EPA-registered formulations of DEET, picaridin, IR3535, OLE, PMD, and 2-undecanone safe for use during pregnancy. According to the EPA, there is no evidence that exposure to permethrin results in adverse effects in pregnant or nursing women or developmental adverse effects in their children.29

- EPA. Repellents: protection against mosquitoes, ticks and other arthropods. Available at: https://bit.ly/3HIvk52. Accessed June 18, 2025.

- QD Nguyen et al. Insect repellents: an updated review for the clinician. J Am Acad Dermatol 2023; 88:123. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.10.053

- N Giangrande et al. Anaphylactic shock to a DEET-containing insect repellent. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2021; 31:336. doi:10.18176/jiaci.0644

- ZM Haleem et al. Exposure to N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide insect repellent and human health markers: population based estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2020; 103:812. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.20-0226

- H Ghali and SE Albers. An updated review on the safety of N, N-diethyl-meta-toluamide insect repellent use in children and the efficacy of natural alternatives. Pediatr Dermatol 2024; 41:403. doi:10.1111/pde.15531

- L Goodyer and S Schofield. Mosquito repellents for the traveller: does picaridin provide longer protection than DEET? J Travel Med 2018; 25(suppl_1):S10. doi:10.1093/jtm/tay005

- MRG Fernandes et al. Efficacy and safety of repellents marketed in Brazil against bites from Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus: a systematic review. Travel Med Infect Dis 2021; 44:102179. doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2021.102179

- NP Charlton et al. The toxicity of picaridin containing insect repellent reported to the National Poison Data System. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2016; 54:655. doi:10.1080/15563650.2016.1186806

- SP Frances et al. Comparative field evaluation of repellent formulations containing DEET and IR3535 against mosquitoes in Queensland, Australia. J Am Mosq Control Assoc 2009; 25:511. doi:10.2987/moco-09-5938.1

- L Goodyer et al. Characterisation of actions of p-menthane-3,8-diol repellent formulations against Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2020; 114:687. doi:10.1093/trstmh/traa045

- B Colucci and P Müller. Evaluation of standard field and laboratory methods to compare protection times of the topical repellents PMD and DEET. Sci Rep 2018; 8:12578. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-30998-2

- CR Connelly and JE Gimnig. Mosquitoes, ticks, and other arthropods. April 23, 2025. CDC Yellow Book: Health Information for International Travel, 2026. Available at: https://bit.ly/4n2rVOn. Accessed June 18, 2025.

- BE Witting-Bissinger et al. Novel arthropod repellent, BioUD, is an efficacious alternative to DEET. J Med Entomol 2008; 45:891. doi:10.1093/jmedent/45.5.891

- BW Bissinger et al. Novel field assays and the comparative repellency of BioUD, DEET and permethrin against Amblyomma americanum. Med Vet Entomol 2011; 25:217. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2915.2010.00923.x

- CDC. Vector-Borne Diseases. Press kit: nootkatone. April 24, 2024. Available at: https://bit.ly/3SRhgsj. Accessed June 18, 2025.

- EL Siegel et al. Ixodes scapularis is the most susceptible of the three canonical human-biting tick species of North America to repellent and acaricidal effects of the natural sesquiterpene, (+)-nootkatone. Insects 2023; 15:8. doi:10.3390/insects15010008

- M Fernandez Triana et al. Grapefruit-derived nootkatone potentiates GABAergic signaling and acts as a dual-action mosquito repellent and insecticide. Curr Biol 2025; 35:177. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2024.10.067

- TC Clarkson et al. Nootkatone is an effective repellent against Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. Insects 2021; 12:386. doi:10.3390/insects12050386

- HA Luker et al. Repellent efficacy of 20 essential oils on Aedes aegypti mosquitoes and Ixodes scapularis ticks in contact-repellency assays. Sci Rep 2023; 13:1705. doi:10.1038/s41598- 023-28820-9

- S Mitra et al. Efficacy of active ingredients from the EPA 25(B) list in reducing attraction of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) to humans. J Med Entomol 2020; 57:477. doi:10.1093/jme/tjz178

- K Daftary and W Liszewski. Allergenicity of popular insect repellents. Dermatitis 2023; 34:70. doi:10.1089/derm.0000000000000897

- L-M Yiin et al. Assessment of dermal absorption of DEET-containing insect repellent and oxybenzone-containing sunscreen using human urinary metabolites. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2015; 22:7062. doi:10.1007/s11356-014-3915-3

- B Londono-Renteria et al. Long-lasting permethrin-impregnated clothing protects against mosquito bites in outdoor workers. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2015; 93:869. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.15-0130

- C Mitchell et al. Protective effectiveness of long-lasting permethrin impregnated clothing against tick bites in an endemic Lyme disease setting: a randomized control trial among outdoor workers. J Med Entomol 2020; 57:1532. doi:10.1093/jme/tjaa061

- RV Patel et al. EPA-registered repellents for mosquitoes transmitting emerging viral disease. Pharmacotherapy 2016; 36:1272. doi:10.1002/phar.1854

- KM Sullivan et al. Bioabsorption and effectiveness of long-lasting permethrin-treated uniforms over three months among North Carolina outdoor workers. Parasit Vectors 2019; 12:52. doi:10.1186/s13071-019-3314-1

- W Bao et al. Association between exposure to pyrethroid insecticides and risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality in the general US adult population. JAMA Intern Med 2020; 180:367. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.6019

- SD Rodriguez et al. Efficacy of some wearable devices compared with spray-on insect repellents for the yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti (L.) (Diptera: Culicidae). J Insect Sci 2017; 17:24. doi:10.1093/jisesa/iew117

- US Environmental Protection Agency. Repellent-treated clothing. March 6, 2025. Available at: https://bit.ly/3gERGD4. Accessed June 18, 2025.